MORE: Opioid overdoses followed auto plant closures, study says

“Our study shows that this change in the Ohio law allowed pharmacists to have more opportunity to participate in the management of patients addicted to opioids,” study’s lead faculty researcher Pam Heaton, a professor of pharmacy practice at UC’s Winkle College, said in a press release.

The study was published Jan. 31 in JAMA Network Open. The study was funded by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

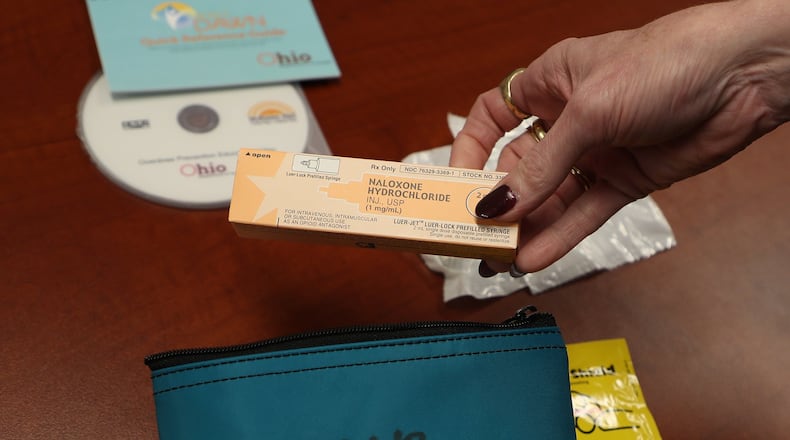

Naloxone, also known as Narcan, is a medication called an opioid antagonist that is used to counter the effects of opioid overdose, such as with morphine and heroin. The majority of states allow pharmacists to dispense the medicine without a prescription under varying guidelines.

As of May 2019, approximately 75% of community pharmacies in Ohio were registered to dispense naloxone without a prescription.

MORE: Miami-Luken case raises questions of who is responsible for opioid crisis

In the study, the research team compared 18 months of post-policy data to pre-policy data from Ohio’s Medicaid records and the database of the Kroger Co.’s Ohio pharmacies, which includes prescriptions for patients with all types of insurance, not just Medicaid. Ohio’s Medicaid population is approximately 2.2 million, or 21% of the state’s population of 11.42 million.

Among Medicaid recipients, the total number of patients receiving naloxone increased from 183 patients in the pre-policy period to 3,847 patients in the post-policy period.

The analysis using the Kroger data confirmed an increase in the number of naloxone prescriptions dispensed for all types of insurance including cash prescriptions.

Researchers also found that low-employment counties had 18% more naloxone prescriptions dispensed per month compared to high employment counties.

Heaton said the uptick in low employment areas is most likely because the local pharmacy is often the sole health care contact for people living in these locations.

“We do not know whether the naloxone was for personal use, a family member or a friend because the law was written to specifically allow access,” Heaton stated.

Heaton said the study did not seek to quantify the impact of increased naloxone distribution on the rate of opioid abuse or mortality from overdose, but was designed to address access.

About the Author