Darnell Jr. nodded: “He was just so nervous.”

“He knew what was at stake,” Michael said. “He knew the historical connotation, the stereotypes, the vitriol … it wasn’t just a game that night, it was an important event for every African-American.”

The championship game of the NCAA tournament that night pitted Texas Western — which would start five black players, something unheard of in Division I basketball back then — against No. 1 Kentucky, the blue-blood program with the lily-white team of Adolph Rupp.

Darnell Sr., a Clark County deputy sheriff, would watch the game in the basement of the family’s home on Lexington Ave. in Springfield’s East End. That where he kept the Zenith color console he’d won a few years earlier — an acquisition that made the Carters the envy of the rest of the neighborhood whose TV sets were all black and white.

Even so, the Carter brothers — Darnell was 13, Michael was a couple months shy of 6 — wouldn’t be watching the game with their dad and the other older family members who came over.

“The game was late and our parents were strict,” Michael said. “We had to go to bed.”

Regardless, the boys discussed the possibilities of the night in the darkness of the bedroom they shared. But even wild imaginations of youth couldn’t match the glorious reality they discovered in the morning light.

The unfazed bunch from Texas Western — coached by Don Haskins, a man who similarly refused to wilt under pressure and threat — had pushed aside Kentucky, 72-65, and in the process swatted racial presupposition into the cheap seats.

Later that same year, on Nov. 19, the Carter brothers said they did get to watch another historic moment in sports. Notre Dame and Michigan State, whose football teams were unbeaten, met in East Lansing, Mich., for what was billed as “The Game of the Century.”

For African-Americans, this game had social significance as well. The Spartans were quarterbacked by Jimmy Raye, who was black.

“We were more nervous about this game than Texas Western,” Michael said. “This match-up had been on a collision course all year.”

Darnell agreed: “In the NCAA tournament, you don’t know who you are going to play from one day to the next. So the window of excitement was a lot smaller for Texas Western than it was with Michigan State.”

Back then, Michael said, the skewered thinking by many in sports was that a team couldn’t win on football’s biggest stage with a black quarterback, that a white player had the cognitive skills and leadership capabilities necessary in the most pressurized situations.

Michigan State — whose defensive quarterback, so to speak, middle linebacker George Webster, was also black — battled Notre Dame to a 10-10 tie and once again racist misconception was flattened.

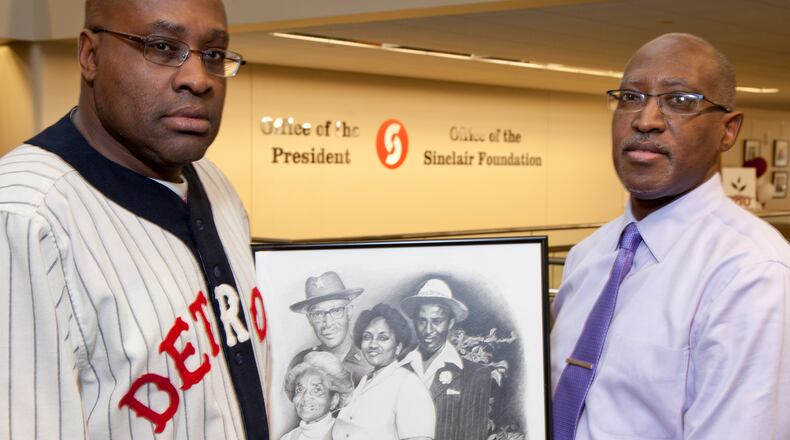

Some of those old memories came to the fore recently when the Carter brothers — Darnell is a Springfield attorney and a tutor at the Keifer Alternative Academy and Michael, the former Trotwood-Madison High basketball coach, is the superintendent of school and community partnerships at Sinclair Community College — taught a class called African Americans in U.S. Sports at the University of Dayton’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute.

The more they thought about 1966, the more they realized they had a watershed year when it came to important events that prompted racial equality in sports. And that has become the basis of a Black History Month free presentation they’ll give at Sinclair on Monday from noon to 1:15 p.m. on the Building 8 stage.

The title is “How Five Hall of Fame Coaches Unwittingly Hastened Integration in College Athletics.”

It will focus on the Texas Western–Kentucky game and the “Game of the Century” between Duffy Daugherty’s Michigan State team and Ara Parseghian’s Fighting Irish. It will also examine what they believe was voter backlash toward an Alabama football team that finished unbeaten but was ranked third in the final polls in part because the Tide had no black players and faced no integrated teams until it was forced to meet Nebraska in the Sugar Bowl.

To help give the presentation context, the Carters will add some of the most remarkable — and in two instances unsettling — stories of skin color and consequence the sporting world has known.

Still great pals

Darnell Carter Sr. and his wife Maxine, both of whom had so much to do with the positive development of their two sons and their daughter Nancy, came from the humblest of beginnings.

Maxine, who was raised in Tulsa and was a small child there during the deadly Tulsa race riot, worked as a domestic early in life. Darnell Sr., later the warden of the Clark County jail, was born in Cynthiana, Ky., where many in the family had worked in the thoroughbred racing barns.

“Our father had a ninth-grade education and our mother finished eighth grade,” Michael said. “But they never showered us with misfortunes they had suffered because of their race. They didn’t want it to embitter us.

“Instead they gave us an interest in history and took us on day trips to every historical site in Ohio. And they promoted education. We visited every college we could — Wilmington, Oberlin, Otterbein, school after school. Each place they bought us a t-shirt and I’d wear mine to school. Behind it all was their belief that education was our opportunity to level the playing field.”

And they were right.

Michael would graduate from Wittenberg University. Darnell got his undergrad degree at Concordia College in Minnesota, his law degree at Drake and his master’s in history at Ohio State.

But long before those diploma days, back when they were still kids, the brothers developed a curiosity about the world that they embraced day … and night.

“We grew up in a great home, but with a pretty strict upbringing,” Michael said. “We shared a bedroom, but even then when it was lights out, it didn’t mean we went right to sleep.”

Darnell agreed: “Sometimes we had a flashlight and we held it under the covers so we could read.”

That made Michael smile: “Darnell, being seven years older, I listened to everything he said. He loved to read so I was his guinea pig. He’d tell me about Native Americans and dinosaurs and sports as we lay in bed. He just told me story after story after story.”

All these years later — Darnell is 60 and Michael is a couple of months shy of 53 — the brothers are still great pals. They talk two or three times a week on the phone about politics, family and sports and they still take excursions.

In May they’re headed to Kansas City to visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum. And each February now — last year the topic was Negro League Baseball — they give a Black History Month presentation at Sinclair.

‘Honor of my race’

Monday’s session on the impactful events of 1966 will get some added depth with a few moving stories from the past, including ones on the embrace of black players by Paul Brown, the 1951 broken jaw assault of Drake’s Johnny Bright on the football field by a thug in an Oklahoma A & M uniform who reportedly was encouraged by coaches, and the courage of Mississippi State basketball coach Babe McCarthy, who defied local lawmakers and snuck his all white team out of the state to play a Loyola team with four black starters in the 1963 NCAA tournament.

But the Carters’ most heart-wrenching is about Jack Trice.

Born in Hiram and graduated from Cleveland East Tech, Trice was the first African-American athlete at Iowa State. The night before his 1923 college debut against Minnesota, he was forced to stay in a “colored-0nly” hotel in Minneapolis, while his white teammates lodged elsewhere.

The next day, on the second play of the game against the Gophers, his collarbone was broken, but he insisted on continuing to play. In the third quarter, he was trampled by three Minnesota players and seriously injured. Although he wanted to keep playing, he was sent to a local hospital, only to have doctors release him saying he was okay.

He returned by train to Iowa and died two days later of hemorrhaged lungs and internal bleeding.

Just before his funeral, a handwritten letter — a copy of which the Carters have — was found in his pocket. He had written it the night before the Minnesota game in his hotel room. It began:

“To whom it may concern:

“My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will!

“My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped I will be trying to do more than my part.”

About the Author