By Ann Heller

Time caught up with the old King Cole.

The merriment, which was mostly just a memory in recent years, will be silenced Saturday night when the restaurant serves its last supper.

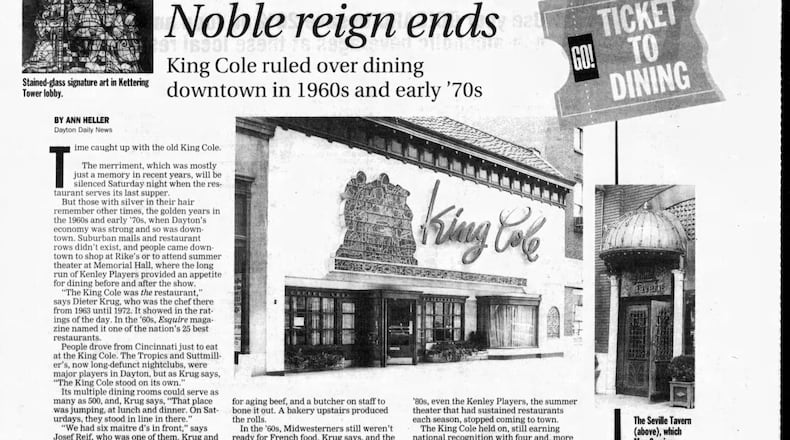

But those with silver in their hair remember other times, the golden years in the 1960s and early ’70s, when Dayton’s economy was strong and so was downtown. Suburban malls and restaurant rows didn’t exist, and people came downtown to shop at Rike’s or to attend summer theater at Memorial Hall, where the long run of the Kenley Players provided an appetite for dining before and after the show.

Credit: Dayton Daily News archives

Credit: Dayton Daily News archives

“The King Cole was the restaurant,” says Dieter Krug, who was the chef there from 1963 until 1972. It showed in the ratings of the day. In the ’60s Esquire magazine named it one of the nation’s 25 best restaurants.”

People drove from Cincinnati just to eat at the King Cole. The Tropids and Suttmiller’s, now long-defunct nightclubs, were major players in Dayton, but as Krug says, “The King Cole stood on its own.”

It’s multiple dining rooms could serve as many as 500, and, Krug says, “That place was jumping, at lunch and at dinner. On Saturday’s they stood in line in there.”

“We had six maître d’s in front,” says Josef Reif, who was one of them. Krug and Reig, now owners of l’Auberge in Kettering, were drawn by Max Comisar, who founded the King Cole.

“He was one of the top restaurateurs I ever worked for,” says Krug, who worked at the Maisonette and numerous restaurants in Europe before coming to the King Cole. “His favorite phrase was ‘There’s no substitute for quality.’”

In the kitchen there was a special room for aging beef, and a butcher on staff to bone it out. A bakery upstairs produced the rolls.

Credit: Dayton Daily News archives

Credit: Dayton Daily News archives

In the ’60′s, Midwesterners still weren’t ready for French food, Krug says, and the King Cole served a lot of steaks and prime rib.

“But he didn’t hire me to cook prime rib,” Krug said of Max Comisar. “He wanted more.”

It showed in the fine art that graced the walls, in the crystal chandeliers, in the menu of fare that was called “Continental.”

The hand of fate wrote furiously in the mid ’70s. In the fall of 1974, Comisar died and his place was taken by his son Bruce. It was just months before the development of Courthouse Square forced the King Cole’s eviction from the L-shaped space that wrapped around the corner building at Second and Ludlow streets – the corner where Comisar had operated restaurants since 1928.

In January 1975, the restaurant moved to the Kettering Tower, hidden from street view, accessible only through a sterile bank lobby.

Things were never quite the same, for the restaurant and, it turned out, for the city. It was a time of rapid and irreversible change. Dayton’s industrial base started to crumble, with NCR scaled back to a skeleton of its onetime work force of 20,000. Frigidaire became history.

Downtown, stores closed or were bought out – and then closed by disinterested owners.

Suburban restaurants opened to serve residents who had fled the city. And in the ’80s, even the Kenley Players, the summer theater that had sustained restaurants each season, stopped coming to town.

The King Cole held on, still earning national recognition with four and, more recently, three stars from Mobil Travel Guides. But its bustling days were over.

The 45-year-run came to a close slowly and painfully. Last summer, empty dining rooms forced the restaurant to cut dinner service to just three nights a week.

Saturday, the restaurant will serve its last meal – a sold-out $100-per-person menu for 170 guests. They will dine on lobster and Dover sole and veal medallions and drink champagne from souvenir glasses specially etched with the 1953 opening and 1998 closing dates of the restaurant.

The King Cole name, the paintings and any pieces bearing the restaurant name will be removed Sunday. They remain the property of Comisar. The space, the building owners say, will reopen Monday as another restaurant with a new manager.

If they’re smart, it will be a concept for the ’90s.

Fine dining and crystal have lost their appeal to a cool generation that doesn’t even want to dress for dinner. Paintings on the restaurant wall are likely to be the work of a virtually unknown local artist rather than Gainsborough. The cover on the table is more likely to be paper than cloth. And the diner tastes run to salsa rather than sauce.

It is a different time, and time to bow to the change. So let the fiddlers play on, only make it a different tune.