The Dayton Daily News talked to school administrators, transportation supervisors and parents like Bogle to assess the busing situation at area school districts. Our reporting found:

• Parents are frustrated, largely by frequent schedule changes that force them to rearrange their work and family schedules.

• Ohio has seen a 20% drop in available bus drivers since before the pandemic. Pay and unusual hours are factors.

• Districts such as Franklin and Huber Heights have eliminated high school busing due to budget cuts.

• Cities like Kettering say homelessness is increasingly contributing to the problem. Schools are forced to send buses across the county to pick up kids staying in shelters or with others.

• Laws requiring transportation to charter and private schools stretch resources thin. Dayton Public Schools has 14 buildings of its own, but has to transport students to 21 charter and private school buildings.

The struggles that parents have are evident in the long lines at school pickup, and the signs near every school in the area advertising bus driver positions.

Bogle said last year she and her two third-grade students were waiting for the school bus at 5:55 a.m..

“They definitely didn’t love it,” Bogle said. “It was difficult and it was harder when it was cold. It was like, OK, all right guys, bundle up, let’s go out.”

To deal with the situation, Bogle told the kids that it was an adventure. Eventually, she did get a more reasonable pickup time.

Her kids go to Ruskin Elementary in Dayton, which starts at 7 a.m. Dayton Public Schools administrators say their start times for elementary are different than most districts — 7 a.m. for about half the schools, and 9 a.m. for most of the others — because of the need to bus charter and private school students, who mostly start school at 8 a.m. (River’s Edge Montessori and Charity Adams Early Academy, both DPS magnet elementary schools, start at 8 a.m.)

Private, charter school growth

Under Ohio law, students in grades K-8, who live more than two miles away from school, must be transported, with some exceptions.

A 1965 law requires public schools to offer busing to all students living in the district, whether they attend public, private or charter schools. This law was controversial from the start, with Protestant Ohioans worried about paying for Catholic schoolkids to go to school, according to Dayton Daily News stories at the time.

Credit: DaytonDailyNews

Public schools can declare private or charter school kids impractical to transport, but the schools must pay the families of those children between approximately $600 and $1,200 to get their children to school themselves. Last fall, Ohio Attorney General David Yost sued Columbus City Schools over the number of students declared impractical to transport.

“With all the additional private, parochial, non-public and charter schools that are out there — and those numbers keep rising — it makes it more challenging for districts to provide services not only just for the public schools, but also for all the private and parochial schools,” said Todd Silverthorn, school transportation director of Kettering City Schools.

Credit: Bryant Billing

Credit: Bryant Billing

Since the early 2000s, when Ohio’s EdChoice movement started, Ohio’s public schools have fought against the wave of students who are choosing to attend charter schools — which are public schools not administered traditionally — and private schools, many of which are run by the Catholic Church in this region.

In 2023, an Ohio budget bill expanded access to EdChoice. Ohio families who want to use EdChoice can qualify for the full scholarship with incomes up to 450% of the state’s poverty line, which is more than $130,000 for a family of four in 2025. Families with incomes above that limit can still qualify for at least 10% of the scholarship.

Private and charter school families also struggle to get transportation for students.

Jessica Routely, the parent of a Dayton Regional STEM School student, said she usually has to get a grandparent to pick up her daughter from school as she and her husband both work full-time.

“I’m fortunate to have flexibility in my job which allows this to work for us,” Routely said. “It would be nice to have the option to have her ride a bus home from school.”

Other factors

Another reason school districts may have to transport kids outside of their normal footprint is the growing population of homeless students, Silverthorn said.

Kettering City Schools currently has about 35 homeless students enrolled. Under Ohio law, districts are required to provide transportation up to 30 minutes away for their students, so a Kettering student whose family lost their home and is staying with relatives in Tipp City must be transported by Kettering buses.

Then there is the shortage of school bus drivers.

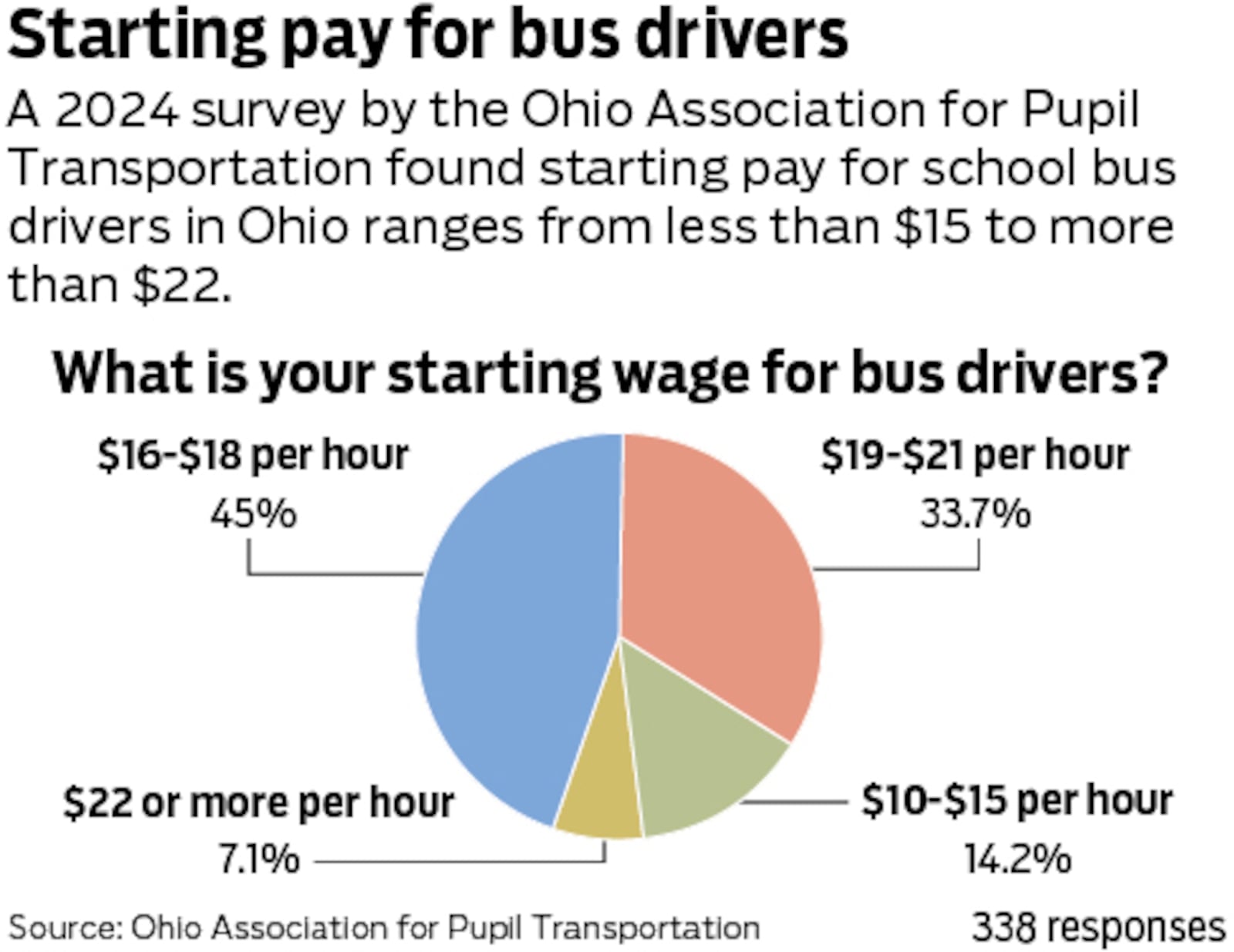

Silverthorn has been in school transportation for more than 20 years and previously was president of the Ohio Association for Pupil Transportation. He said there’s been a long-term shortage of bus drivers. This year, there are 20,541 Ohio bus drivers, compared to 25,706 bus drivers in 2019.

This competition drives up the cost of drivers. Dayton Public Schools says they finally have enough drivers, but to do this they pay among the highest rates in Ohio.

‘A great burden’

Some districts, like Franklin and Huber Heights, stopped offering busing for high school students after dramatic cuts to their budgets.

Cassie Clark, a Franklin Junior High parent, said she has been leaving work at around 2 p.m. every day to pick up her kid. Their home is about two miles from the school, the radius at which Franklin cut off transportation for students. Her older child attends Franklin High School, and since Franklin no longer offers busing at the high school either, it makes it even more difficult.

“There’s a lot of people that are impacted by this, waiting in lines to pick their kids up,” Clark said.

Michael Sander, the district’s superintendent, said budget cuts have made cutting busing necessary. Passing a levy would bring busing for high school students back, he said. The most recent levy in November, which would have brought $6.3 million annually to the district, was rejected by voters.

“It is a great burden on our parents and students to not have busing,” Sander said.

Jason Enix, the superintendent for Huber Heights, noted that busing for high school hasn’t been offered since around 2014, when the district went through multiple rounds of cuts.

Absenteeism impact

Enix said many high school students walk to Wayne High School, but others get rides with other students, from their parents or even take the Greater Dayton Regional Transit Authority bus.

Enix said it’s not clear if the district’s chronic absenteeism rate – the number of students missing 10 or more school days – would improve if the district was able to offer bus rides to high school students. He said there is demand for those services, especially freshmen and sophomores who may not have a driver’s license, but in his experience at other districts, there were often fewer students on high school buses.

“Oftentimes, those buses ... for high school were way less than half full,” Enix said. “Because so often, kids either have after school activities, or it’s not cool to ride a bus and they are going to ride with friends.”

A 2021 Wayne State University study looking at students in Detroit found that while transportation access can be a barrier for students to get to school, complicated family schedules, weak social networks and unsafe conditions also contributed to chronic absenteeism.

DPS has ‘some work to do’

Dayton Public has been the focus of busing woes as it is both the largest district and has the highest number of students being bused each day to various schools across Dayton, Kettering and Trotwood.

About half of the school-age kids in the district attend Dayton Public, and the other half attend an array of charter and private schools around the region.

Dayton Public transports students to 21 different charter and private schools around the region each morning, as well as to the Montgomery County Educational Service Center’s locations, which services students with high needs. Dayton Public has 14 buildings of its own.

Dayton Public has had significant issues getting students to school on time. In 2022, Ohio fined Dayton Public after several charter and private schools alleged district buses were late both dropping off and picking up students. One administrator at a Kettering private school wrote, “I don’t know that they know what a busing plan is.”

Transportation for DPS high school students was thrown into disarray earlier this year when state lawmakers tried to ban them from changing buses at the RTA hub downtown. But that bill is on hold pending a lawsuit from DPS.

DPS Superintendent David Lawrence says the district has finally recruited enough drivers, but there is a long way to go. He says the system of busing, communication, and how the district interacts with parents and kids in the community is still a big, thorny problem.

“We’ve got some work to do,” he said. “It’s not enough to just keep saying we have enough drivers, and we’re picking kids up and dropping them off on time. That’s the bare minimum.”

About the Author