Even local schools who aren’t legally required to restrict cell phone use during school hours are doing so, citing concerns from teachers and observances from their own students.

High schoolers themselves have said they notice the downsides of constantly having a communication device, though many say they wish schools could teach them how to use the device better.

What’s fascinating about the rapid shift in media use is that kids and adults alike seem to understand that the rapid change in cell phone use post-COVID is not good for us. But teens and adults don’t agree on exactly how to change the rules to make them work for everyone.

And without teenagers’ buy-in, these strategies aren’t going to work.

Under a new Ohio law, public and community schools are required to adopt a policy emphasizing students should be using cell phones as little as possible during the school day and reduce cell-phone related distractions during the school day. The policy doesn’t ban cell phones entirely and leaves a lot of leeway up to the individual district.

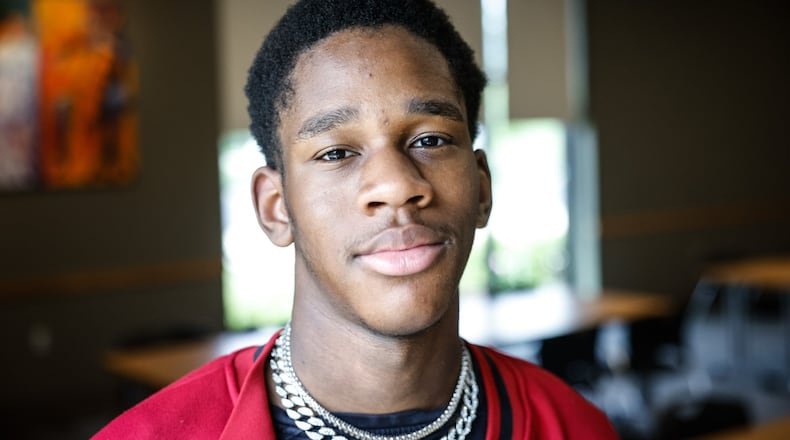

Trotwood-Madison student Gerry Smith, who is going into his sophomore year, said problems between some of the students at his school started online on social media, and got worse at school.

“There’s like a lot of people just fighting online using words and they bring it to school,” Smith said. “And it’s crazy because all this is happening on social media.”

Smith said using Yondr pouches, which require a special magnetic key to remove phones from, was helpful to keep kids on task. But there were still kids trying to take them out of the pouches themselves, which makes sense if a teenager feels someone’s taking something away from them unfairly.

The Miami Valley School, which is an independent, private school not covered by the new law, is changing its policy next year to collect phones in the morning and return them to students at the end of the school day.

“When I’m observing class, and I’m seeing students check their phone, I know that that’s taking away from their learning environment,” said Blair Munhofen, head of the upper school, which is grades nine through 12 at MVS. “Teachers are sick of this thing that is essentially an appendage of the student.”

A similar policy is already in effect at the MVS middle school, he noted.

“I just wish we had done it sooner,” Munhofen said. “But I think we were also trying to just manage getting out of the pandemic.”

He said MVS had tried to work with students on cell phone use and healthy boundaries, but it didn’t work as hoped.

Similar reasoning prompted West Carrollton schools to implement a no cell phone policy at the intermediate, middle and high schools as a pilot during the 2023-2024 school year, said Janine Corbett, spokeswoman for the district.

“District students were no longer distracted by calls and/or text messages during the school day. Unintentional benefits were increased instructional time, positive student interactions, and a decrease in office referrals by 33% or more,” she said.

Shannon Cox, the Montgomery County Education Services Center superintendent, said the use of phones has changed since the pandemic. Some teachers want students to use their phones in their classes.

But there were always issues with that, because some kids had limited data plans or no cell phones at all.

There was always pushback from parents in wanting to keep cell phones with students, Cox said, because there are some kids who have long sports practices and need to be able to contact their parents afterwards, or their student takes the RTA and has multiple bus transfers.

It’s important to note there are positives in a cell phone. The American Association of Pediatrics says to limit screen time use almost entirely for babies and toddlers, except for video calling with family members. Older kids can text and call their friends or keep in contact with their family. Smith, for example, formerly attended a school in Columbus, and said he’s always texting or calling his friends.

But a rise in cyberbullying and mental health issues post-pandemic has left some school officials believing the best way forward is very limited cell phone use in the school building.

“We are under psychological threat every single day because it’s so easy to say negative things,” Cox said. “And it’s so easy to consume negative material, because it’s at your fingertips 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

She noted that students on the advisory board for the ESC have said they were interested in learning about creating healthy boundaries in their phones.

Dr. Ryan Sinclair, a pediatric psychologist at Dayton Children’s Hospital, said positive role modeling from adults is key for kids learning more about how to use phones effectively.

Creating phone-free zones – like blocking phones in the bedroom – are important for kids, Sinclair said.

“I work in our sleep clinic, and gosh, that’s probably one of our primary conversations we have is around screen usage and especially how it can affect sleep,” Sinclair said. “We discuss the some of the negative implications that can result from using screens in the bedroom, such as developing unhealthy associations with our bed.”

Sinclair said using phones in bed makes an association, meaning when people get into bed, they automatically want to use a cell phone.

“Ultimately, it’s trying to get the teenagers to see some benefit and making some changes,” Sinclair said. “If they’re able to share with me some of the benefits that they can see, we tend to have better success.”

Guardians who want to limit more social media use for kids can start with the American Association of Pediatrics’ Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health, which includes conversation starters, ways parents can curb their own use and more.

About the Author