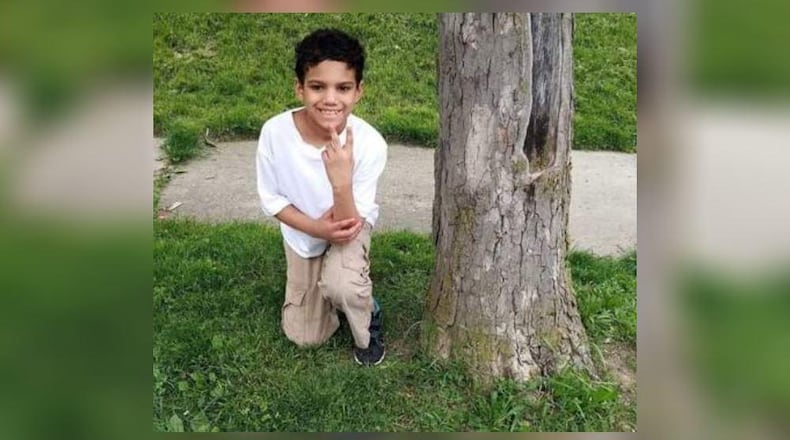

Takoda died at Dayton Children’s Hospital in December 2019. Investigators say his father, Al-Mutahan McLean, tortured him for years: locking him in an attic, forcing him to stand bent over and cross-legged for long periods, and beating him. Takoda’s death was ruled a result of blunt force trauma and drowning in a bathtub.

In September 2021, McLean and his girlfriend pleaded guilty to causing Takoda’s death.

Plummer, who was Montgomery County sheriff until the end of 2018, called Takoda’s death horrific and said it prompted him to introduce his bill to reform county children’s services operations.

HB 4 passed the House 92-2 in May and came before the Senate Judiciary Committee for a second hearing on Tuesday, where three supporters submitted written testimony.

Paul Pfeifer from the Ohio Judicial Conference noted that HB 4 would expand the list of people who can carry out assessments of foster care and adoptive homes. Juvenile court intervention would protect parental rights too, by quickly closing the case if allegations are unfounded, he wrote.

Mary Wachtel from Public Children Services Association of Ohio said bill sponsors accepted several changes from her group. She supported creation of an ombudsman’s office in particular.

Angela Earley from Chrysalis Family Solutions, who described herself as a former foster parent and adoptive parent of three special needs children, also lauded creation of an ombudsman position as an independent check.

“While most child-serving staff act in the best interests of children and families in care, mistakes are made and unnecessary extensions of time are permitted with no unbiased oversight,” Earley wrote. “If children or families have a grievance, there is rarely a third party involved. These cases are almost always reviewed by the agency staff, which leads to withheld justified complaints for fear of retaliation and/or biased protection of the agency or agency staff. There is currently no mechanism for impartial representation.”

A Dayton Daily News investigation found that police were called to Takoda’s home multiple times for more than a year before his death. An employee of Dayton Public Schools and a caseworker for Montgomery County Children Services both told police they suspected Takoda was being abused.

Following those reports, police noted there was “no answer at the door” and closed the call. Police later said the officers dispatched were not notified of the abuse allegations.

Prompted by the newspaper’s investigation, Dayton police and children services implemented new policies.

The police department is now mandating that officers complete a memo when they are called to do a welfare check in addition to contacting children services. Police must also follow up if no one answers the door during a welfare check.

Children services now requires that all members of a household must be spoken to, whoever reported abuse or neglect must be contacted afterward, and that case histories are explored.

About the Author