Marco Antonio's case was particularly rare. His mother brought him to the United States when he was 5 months old and never registered his birth with the Mexican government. With no birth certificate from his native country and no identifying documents from the country where he grew up, Marco Antonio had lived his entire life with no official government identity.

If the consulate approved him for the passport, it would help him apply for a special immigration relief in the United States for children neglected or abandoned by a parent. Last year, Marco Antonio lost contact with his father, who was working in Washington state.

Cases like Marco Antonio's are few -- the Mexican Consulate in Austin had seen no more than three since 2012 -- but they shed light on an immigration tactic that Mexican officials are using increasingly in recent years to help undocumented immigrants gain an official identity in this country and improve their immigration status.

Critics, however, are concerned that these protective passports are being issued by a foreign government to remedy someone's immigration status.

"The point of this document is to enable someone to get home when they are stranded," said Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Washington-based Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for stricter enforcement of immigration laws. "If the document is then being used abroad, then it becomes a problem because it changes the fundamental point of the document."

In the past, people in Marco Antonio's situation were stuck. They could not receive any official documentation from the Mexican government unless they returned to their home country to file the necessary paperwork -- an option that, because of lack of resources and immigration status, was difficult to achieve. And without that documentation, it was almost impossible for them to remedy their immigration status in the United States.

That changed when President Barack Obama put in place the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration policy in 2012. Under the program, undocumented immigrants who came to the country as children could apply for temporary deportation relief from the federal government and be allowed a work permit. But they still needed official documents to prove their identity to federal immigration authorities.

The Mexican government's foreign service jumped at the opportunity to help, asking its consular network to issue protective passports to its citizens in the United States to facilitate the DACA process.

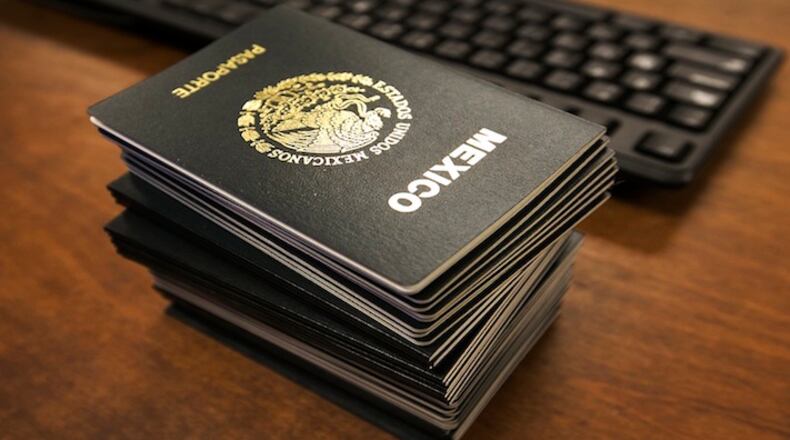

Since then, Mexican officials have issued protective passports to help their citizens obtain the benefits of that policy, as well as other immigration programs like U visas, which are given to victims of crime, or Special Immigrant Juvenile status, which is given to children who have been separated from their parents or are victims of neglect.

In 2015, the Mexican Consulate in Austin issued 140 of those passports. As of this month, the consulate had issued 15 this year, officials said.

But critics, like Krikorian, question the security of these documents. In the past, they have also questioned the security of Mexico's passports and another document called the "matricula consular" (consular card), saying they do not receive enough scrutiny to protect against fraud.

Because applicants for protective passports have even less documentation to support their case, those documents are also less secure, said Krikorian, who referred to them as "passport lights."

"The Mexican government can issue any document they want to," he said. "The question is: What is our approach? Do we recognize it as a full-fledged document?"

The Mexican government stands by its security measures. Carlos Gonzalez Gutierrez, the consul general of Mexico in Austin, said his staff takes "exhaustive measures" to verify the identity of those who receive protective passports because the consulate would stand to lose if a passport were mishandled.

"We would be penally and administratively responsible if we issued a false passport or if we issued a passport to someone who is not who he or she says he is," he said.

In cases like Marco Antonio's, where applicants have no birth certificate, officials have to track down other identifying documents like hospital records, the birth certificates of siblings, vaccination records or even baptism certificates that prove a person is who they say they are and was born in Mexico. Often, investigations to issue these passports take months.

"Our work in providing identifying documents to our citizens in the U.S. is of paramount importance," Gonzalez Gutierrez said. "There is no better way to protect somebody than to issue them the appropriate documentation."

For Angela Aviles, Marco Antonio's mother, it's a way to set up her son for the future. He received his protective passport this month.

"I just want to make sure he has his things in order," said the mother, who brought her son to the United States to give him a better life. "Maybe he can apply for DACA later. For me, this is a great happiness."

About the Author