In large part, Gov. Mike DeWine and Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Amy Acton are using a playbook written more than a century ago as they now respond to the coronavirus pandemic.

In 1918 and 1919, the Spanish influenza pandemic killed 50 million people worldwide, including 675,000 in the United States. Between October and December 1918, 657 Daytonians died of influenza or influenza-related conditions, according to the Influenza Encyclopedia, a digital archive maintained by the University of Michigan Library.

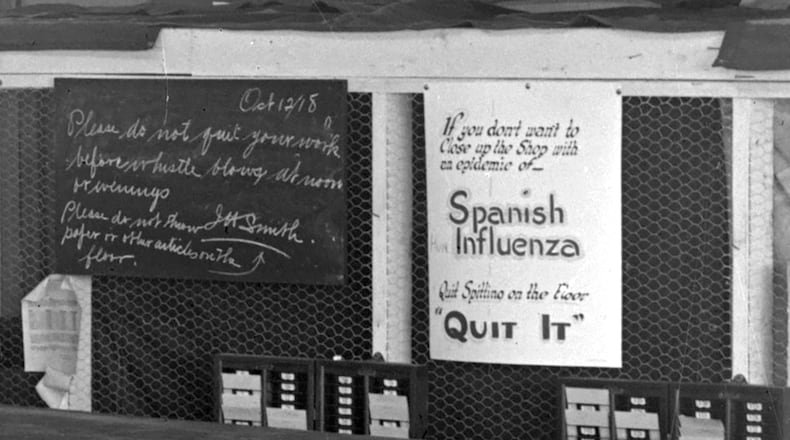

Like now, no vaccine existed then, leaving public health authorities to use closures, quarantines, good hygiene, disinfectant and social distancing to fight the spread.

At the time, Ohio Gov. James M. Cox, founder of the Dayton Daily News, decided to allow local jurisdictions to determine what closures would work best. On Oct. 10, 1918, Cox and his team suggested local health authorities close public places to stop the virus.

“Open air activities such as ball games and other operations that summon people together in the open, are not affected by the order,” read a newspaper story from the time.

The Spanish flu likely started in March 1918 at an Army base in Kansas where 500 soldiers were hospitalized. Soldiers mobilized to Europe for World War I, spreading the virus farther. When they returned, they brought back a mutated, deadly version of the virus, according to Ohio History Connection.

The flu continued to infect soldiers at a high rate. Camp Sherman in Ross County saw 5,686 military personnel fall ill, with 1,777 dying. The Majestic Theater in nearby Chillicothe was used as a makeshift morgue, according to Ohio History Connection.

An early alarm about the Spanish influenza was sounded in the Sept. 23 edition of the Dayton Daily News by Peters, then Dayton’s health commissioner.

“The disease is one of the most virulent known to medical science. It is also readily contagious,” Peters said. He advised patients to “isolate themselves as far as practicable as a protection to the community.”

Daytonians of the distant past were no strangers to quarantining.

By the time Spanish flu crept into the city in the fall of 1918, scarlet fever, tuberculosis and outbreaks of other influenza had pushed the population into isolation.

“It was common practice if you were ill to self-quarantine,” said Brady Kress, president and CEO of Dayton History. “They knew enough as you get into the 20th century that if you had something contagious you don’t go anywhere.”

Dayton built a quarantine hospital in 1887. Called the Pest House, it sat on the site of today’s Carillon Historical Park.

Despite early warnings from Peters, a half-dozen cases of the flu found in Dayton and at Wilbur Wright Aviation Field escalated concerns. The city issued a quarantine order for the sick on Sept. 30, 1918.

“The only known preventative from the spread of this disease is complete isolation of the sick from the well,” Peters wrote to Dayton doctors.

Almost two weeks later, as the disease spread, Peters recommended only one person be allowed to attend to the sick in each household.

Caretakers wore gauze masks saturated with disinfectant and family members used a milk alkaline antiseptic throat and nose wash to ward off the flu.

Advertisements on newspaper pages chronicled shortages of Vick’s Vaporub and pushed remedies for the disease.

Gudes’s Pepto-Mangan, “the red blood builder,” claimed it could fortify your body against Spanish influenza and 20 drops of Hull’s Superlative Compound, “a root and bark remedy rich in Peruvian Bark,” would break a fever.

Visiting nurses in Dayton worked overtime, averaging 15 calls a day. By the end of October, three of the 15 nurses in the city had fallen ill.

“We simply can’t give nursing care to all so all we can do is to have the nurses instruct other members of the families and show them how to give the proper care,” said Elizabeth Holt, then the city’s superintendent of nurses.

By the end of 1918, the disease was subsiding, but by then more than 500 Daytonians had died, said Alex Heckman, vice president of Dayton History.

“That was far more than were killed in the Great Dayton Flood but up until this battle with COVID-19, I think very few people have ever heard of the Spanish flu,” Heckman said.

Records for Woodland Cemetery and Calvary Cemetery show a spike in the number of burials in 1918.

In 1918, there were 1,908 between Dayton’s two largest cemeteries. The year before 1,571 people were buried in the two and in 1919 internments numbered 1,350, according to cemetery records.

“People in 1918 would have unfortunately been accustomed to diseases and early deaths and things we don’t even think about today with modern medicine, drugs and health care,” Heckman said.

But back then, Americans had strong unity around World War I, were accustomed to sacrifice and held a strong belief in science, said Amy Fairchild, dean of the Ohio State University College of Public Health.

“There was an enormous amount of cooperation with social distancing measures,” Fairchild said. “And I think one of the things that we’re seeing now is, not just not being united, but having a polarized society. That is, I think, a public health risk factor for pandemics, too. When we have a lack of trust in government, we have a lack of trust in science, multiple narratives that float around that can have the same kinds of credibility of being true or not true. That can make a difference as well.”